Moonrise Kingdom / Wes Anderson / 2012 /

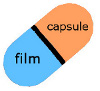

Active Ingredients: Details of the film’s universe; Tenderness; Adventure

Side Effects: Forced climax; Loss of focus on central characters

Much of the storybook visual design and convivial humor of Moonrise Kingdom will feel familiar to fans of director Wes Anderson. While his tender, warmhearted tale of young love and misunderstood eccentrics may not be a stretch for Anderson, there’s enough genuinely new and resoundingly satisfying about Moonrise Kingdom to make it Anderson’s best live-action film in a decade.

Set in 1965 on a quaint New England island, the film is about two young runaways, loners and “problem children” who find a kindred spirit in each other. Sam, an orphan who can’t seem to fit in with his foster brothers, stages a daring escape from Khaki Scout camp armed with a miniature canoe, pounds of sundries and the outdoor survival knowledge his merit buttons signify. Following their meticulous plan, he elopes with the privileged but neglected Suzy, whose attachment to her family ends when she borrows her brother’s record player. They’ve each found in the other the only person who tolerates and understands them, but a boyish Scout maser (Edward Norton) and a lonely police captain (Bruce Willis) are hot on their trail.

Anderson is extremely tender with his pair of misfits and, apart from some ironic, Rambo-style forest adventure, the details of their delicate connection is the film’s greatest joy. Familiarly unfolding like the pages of a worn pop-up book or a beloved dollhouse, Moonrise Kingdom surrounds the children with a cast of adults who represent the world they reject, yet nonetheless exhibit the “emotional instability” they feel they alone suffer from. Aided by fun but melancholy performances from Willis, Norton and Bill Murray, Moonrise Kingdom shows that nobody is without problems. The young lovers may be right to run away together, but they’re far from alone in their insecurities and loneliness.

Moonrise Kingdom fits Wes Anderson perfectly right from its opening extended tracking shot, introducing the rich, diorama-like sets and heightened artificiality that make up its universe. This distinctive visual style has endeared Anderson to his fans and provided ammunition to his detractors (stifling! unrealistic!) since his debut, but I find his brand of symmetrical, detailed graphic design a perfect visual counterpoint to the tragicomic stories Anderson tells. Anderson’s are characters who can only live their own way, and his films are visual celebrations of the beauty and folly of their self-imposed isolation. Despite working with the same cinematographer his whole career, however, Anderson brings new depth and vibrancy to the intricately-composed images of Moonrise Kingdom. Scenes pop with their own color palettes, variations on a common visual theme. Watch, for example, the deep blues and grays in the film’s nighttime finale, or the rich oranges of a dawn canoe ride.

Thematically, too, Anderson finds variations on his common theme of dysfunctional families by juxtaposing Sam and Suzy with the adults in their lives. He beautifully conveys their understanding of the world, but Anderson asks too much of his child actors, making them conform to his tone rather than helping them find a natural artificiality of their own. Perhaps Anderson fares better portraying children when they’re trapped inside a grown-up’s body. Still, Moonrise Kingdom is a film only Anderson could have made, and if you’re a fan on his style as I am, you should be glad he did.

3 comments

Do you want to comment?

Comments RSS and TrackBack URI

Trackbacks