The Grand Budapest Hotel / Wes Anderson / 2014 /

Active Ingredients: Ralph Fiennes; Energy and fast pace; Comedy

Side Effects: Emotional shorthands; Dense plot

Like all of director Wes Anderson’s seven previous features, The Grand Budapest Hotel is an intricate piece of machinery, a minutely calibrated work bursting with detailed design and obsessive symmetry. Like the best of Anderson’s work—among which this film surely belongs—it also demonstrates a masterful command of formal technique, a thoughtful marriage of style and content, and moments of sincere, affecting poignancy.

As much as anything, The Grand Budapest Hotel is a film about storytelling, about the stories we live through, those we tell each other, and those we tell ourselves. It’s a film about the joy we take in these stories, and the sadness they help to conceal. But above all, The Grand Budapest Hotel is a complete delight, fast-paced and fantastical and full of wit and whimsy.

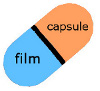

The film is built on a series of nested narratives, each one peeled back like layers of an onion to reveal the heyday of an opulent mountainside resort in 1932, and that of its tireless, foppish concierge, Gustave H. (a deft and revelatory Ralph Fiennes).

Gustave is a total dynamo, demanding to his staff, accommodating to his guests, of questionable sexuality, and never less than excessively perfumed. Among his duties as concierge is to charm, woo, and occasionally bed geriatric widows with heavy purses, and when one such woman dies under mysterious circumstances, leaving all of her fortune to Gustave, he and his ever-faithful lobby boy, the soul of the film, find themselves on the run from her thuggish family and a vampiric hit man.

What ensues is a chase across the hilltops of the fictional Eastern European country of Zubrowka and a series of dazzling comic setpieces in the classic Anderson style. Detractors of this style find it flat, stuffy, and oppressive, but The Grand Budapest Hotel is in fact impossibly fleet and seductive, packed with visual and verbal wit, and the film’s carefully composed layers of artifice justify its staginess. It’s also one of Anderson’s funniest films thanks to Fiennes, whose virtuosic performance breathes life into each line.

Undercutting the many pleasures of The Grand Budapest Hotel, however, is a current of sadness and tragedy. Zubrowka is on the brink of fascism and war, it seems, and while Anderson largely sidelines this darkness, it comes to inflect much of the action. The emotional backstories of Gustave and his lobby boy, again inflected with wisps of sadness, are left similarly vague. Their friendship is touching but Anderson doesn’t develop it with the same sentimental heft of films like Rushmore and Moonrise Kingdom.

Instead, we’re left with a subtle emotional shading to the whole film, one of nostalgic regret for a bygone era. The Grand Budapest Hotel, with its many themes and layers of storytelling, understands that this nostalgia is two-fold: it implies both a fondness for a glorious past, and the profound emptiness left behind in its absence.

Great review.

Thank you very much!